Grounded in compassion and global understanding

Story

(Above photo: Martha Nixon, India, 1964, supplied image.)

Early volunteers reflect on their pivotal experiences and the founders who shaped an organization.

In many ways, one plane ride, back in 1964, set the trajectory for much of Martha Nixon’s life.

She was on her way to India to volunteer with Cuso International at an ashram in West Bengal, on a Department of National Defence (DND) aircraft. This alone was a big leap for her, leaving her small-town Quebec life behind for an adventure abroad.

But it was a turning point in another way, too. On the plane, she found herself seated next to Bill McWhinney, the first executive director of Cuso International following Lewis Perinbam’s early tenure as interim executive secretary.

“It was a long trip and we sat together and talked … about everything under the sun,” says Martha, who was, at the time, in her early twenties and a recent McGill University Arts graduate. “He was certainly an impressive person and had a lot more experience being out on assignment. I was anxious to learn more.”

The plane eventually landed and Martha began her placement at the Abhoy Ashram Basic Education Centre in Midnapore, West Bengal, teaching English and science to young Indian students. She also did “a little bit of everything, gardening and cooking, whatever was needed, as was the way in a Gandhian ashram,” Martha says.

Bill continued on, back to Canada, but the two struck up a long-lasting correspondence that led to Martha returning to Canada earlier than planned. Their marriage soon followed, with Martha holding a close view on Bill’s leadership at Cuso International (then Canadian University Service Overseas, CUSO) and the challenges and successes of the organization at the time.

“Bill was an incredible leader … he was certainly the face of Cuso International for the first few years,” she says.

*

Steve Woollcombe remembers the early Cuso International meetings he attended in 1960, led by Keith Spicer, a University of Toronto PhD student studying Canada’s role in the Colombo Plan (for Economic Development in South and Southeast Asia).

It was Spicer, spurred by a book by Donald K. Faris, To Plow with Hope, who initiated the first overseas placements of Canadian student volunteers through what would soon become Canadian Overseas Volunteers (COV), Cuso International’s forerunner.

“The strongest influence at the beginning was Keith Spicer,” says Stephen, who was studying political science and economics at the University of Toronto, and travelled to India as part of the first COV volunteer cohort. “Those meetings (at U of T) were very exciting … we were really grassroots, and there was no government money at that time.”

To Plow with Hope’s message that young, educated Westerners could provide important skills and service in developing countries lit a fire under Spicer’s feet. Faris underscored that the West could do much more than it was doing through current aid programs and that “what developing peoples needed was assistance in improving their existing ways of life, rather than wholesale transformations based on Western models,” writes Ruth Compton Brouwer in Canada’s Global Villagers: CUSO in Development, 1961-86.

Spicer, who went on to become Canada’s first Commissioner of Official Languages and later, editor-in-chief of The Ottawa Citizen, did not hesitate in bringing his ideas forward to those at the very top of the political food chain:

“Armed with chutzpah and some preparatory notes, Spicer went directly to Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, who readily offered moral and diplomatic support for [his] idea of establishing an organization to send university graduates for a period of service in developing Commonwealth countries,” writes Compton Brouwer.

More fully developed plans followed, and others joined the movement, including Toronto MP Fred Stinson, who became chief fundraiser for COV. Together, Spicer and Stinson brought in sponsorships from newspapers, businesses, churches, and service organizations.

“By the time of the June 1961 meeting at McGill that officially established CUSO, Spicer and a few fellow students, strongly supported by Stinson and a handful of other mentors, had selected fifteen Canadian Overseas Volunteers, put them through a series of preparatory lectures, and had them ready for an August departure for Asia.” (Compton Brouwer)

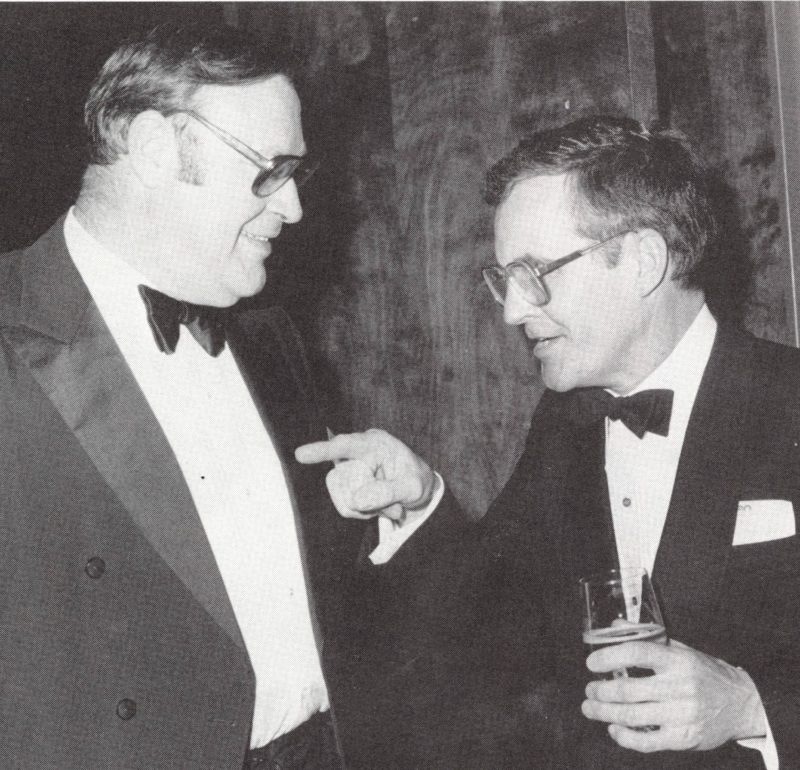

Bill McWhinney, left, and Steve Woollcombe at a Cuso International anniversary dinner in March 1986.

That meeting was preceded by much planning, organization, and toil by many others, including the prospective volunteers themselves. As noted in Compton Brouwer’s history and Ian Smillie’s Cuso International book, The Land of Lost Content, the organization was not the brainchild of any one person and its success was the product of many working simultaneously toward a common goal.

Importantly, it was the early work of Malayan-born, Scottish-educated Lewis Perinbam that helped to create the foundation for the development of Cuso International. Perinbam worked for the World University Service in London and later emigrated to Canada and took a staff position at World University Service of Canada (WUSC). It was his early experiences with WUSC, and his interest in a volunteer plan brewing among the Australian WUS committee, that solidified his drive to develop a more robust Canadian volunteer program.

Volunteer programs were brewing and beginning all over the globe, with the U.S. Peace Corps officially signed into existence by President Kennedy in March 1961, a few months before Cuso International’s official establishment. (Cuso International alumni, however, are quick to note that Cuso International came first, and volunteers were out on placement before Peace Corps volunteers.)

Perinbam moved on from WUSC to work with UNESCO as Secretary General of the Canadian Commission and connected with Dr. Francis Leddy, a dean at the University of Saskatchewan and the President of the Canadian UNESCO Commission. Together, along with others, they developed and drafted a constitution for a national volunteer program, a plan that would bring together universities and other organizations.

Spicer’s COV efforts and Perinbam’s and Leddy’s plans for Cuso International initially clashed, with Spicer opposed to a university-based organization and Leddy looking at COV as “parochial and amateurish,” Smillie writes. But, in a moment of unity at the McGill meeting in June 1961, plans to join the two, and CVSC (Canadian Voluntary Commonwealth Service) finally came together.

“There was an anxious moment of silence. Then a young woman in the audience stood and spoke. She said that she had recently spent two years in Afghanistan and had arranged everything, including the costs, herself. She had often wondered what might have happened had she become ill away from home, without support; and she talked of the need for more of what COV was doing and of what CUSO proposed to do,” Smillie writes in The Land of Lost Content.

“When she sat down, the President of the University of Alberta, Walter Johns, quickly stood and moved that Canadian University Service Overseas be established. The motion was accepted, and the vote was called without further discussion.”

*

Bill McWhinney – or “Big Bill” as he was known, for his 6’7” stature, was asked to return from Sri Lanka (Ceylon), where he was on a bank placement, to lead Cuso International. He was an ideal choice as a bridge-builder, writes Compton Brouwer, as he was “endowed with the gravitas and business training to impress university administrators, government officials, and potential donors, but linked by his youth and shared overseas experience to his fellow volunteers.”

Martha says it was amazing to watch him in operation, because he understood all facets of the organization and what was needed from different sides.

“He was a master at calming worried parents … he’d always take calls from them and bring packages to volunteers when he would go on field visits. Everyone really appreciated his very personal connections,” says Martha, who had two children with Bill. “He was able to connect with all layers of government and worked well with the Board. There was a fair amount of juggling to be done.”

Bill was the one, too, to convince the Pearson government to allow Cuso International volunteers to travel on DND planes to their placements, as Martha did on her way to India, with Bill seated next to her. In the early days, this saved Cuso International a major expense, she says.

Bill stayed on as executive secretary from 1962 to 1966, before moving on at the request of Prime Minister Pearson to set up and run the Company of Young Canadians volunteer agency, and later to other senior positions at the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) and the World Bank. (Perinbam would later work at CIDA, as well.) Martha worked for a time as executive assistant for Hugh Christie, executive director of Cuso International in 1967-68 (following Bill’s tenure and Terry Glavin as acting executive secretary in ’66-’67), and later went into the federal public service, particularly supporting immigration services and other social programs across Canada.

“I really believed in public service … I wanted to deliver programs that would enhance the lives of Canadians.”

*

Reflecting on her volunteer experience, Martha says it was the best thing she ever did.

“It opened the world to me, and I was so grateful to be so graciously received in the ashram,” she says. “The West Bengali people were so proud of their culture and language and they did their best to teach me about it as much as they could.”

What she learned was just as important as the support she was able to provide, she says. Interviewed following her placement, she said: “It’s not so much that I can help but that there’s so much for me to learn.”

That was a founding principle, as Smillie, also an alumnus and an early Cuso International executive director (from 1979-1983), writes in his book. Perinbam, he says, “would always believe that the development of cross-cultural understanding – and caution – were as important an ingredient in international programs as any other.”

“Cuso International gives you huge recognition that we live our little lives here in Canada and many of us are very privileged to have the lives that we have … It teaches us that there is a whole lot of world out there that needs to be understood and we need to be open to the things that have happened in the world and to do what we can to make change,” says Martha.

For Steve Woollcombe, his volunteer experience was equally pivotal, and shaped much of his life.

“It was the ‘60s … the opportunities were boundless, the world was opening up,” says Steve, who taught English and geography to 11-14-year-olds in Ahmedabad. “A great deal of what I am can be sourced back to India.”

For the last six months of his posting, Steve served as Cuso International coordinator in Delhi. Over the rest of his life, he returned many times to India. The first time, 15 years later, was with his wife, a former Peace Corps volunteer, when they adopted a baby girl, Dharini. Two decades after that, Steve joined many of the early India volunteers for a reunion there, and fell in love with the woman who later became his second wife – Judy Barber, a 1963 volunteer in India.

In the meantime, Steve had a lengthy career in the foreign service, much of it in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, noting that his time as a volunteer in India provided a strong foundation for all that followed. His final Cuso International assignment was in 2009, in Cameroon.

For Martha, as for many early volunteers and founders, Cuso International remained an important thread throughout her life. While she and Bill divorced after nine years together, they remained friends until his death in 2001. And she still connects regularly with fellow volunteers (over Zoom during the pandemic; for globally inspired dinners in the before times), all marked by their experiences.

“I’ve always felt that Cuso International gave me a grounding in empathy,” she says. “It helped me to see the world from other people’s perspectives and to look beyond my own narrow interests.”