Parents and practitioners see positive changes in maternal care

Story

Walking into the maternity ward at a hospital in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Bénédicte Lekulangayi could tell things were different.

“When I came to give birth the first time two years ago, I wasn’t treated with a lot of affection. This time, there have been big changes,” says the young mother of two, pictured above. “They take care of us now and tell us to eat when we’re hungry. The washrooms are even cleaner. We really admire the efforts they’re making.”

Since the beginning of the Midwives Save Lives (MSL) project in 2016, more than 250 midwives in the greater Kinshasa area have participated in respectful maternity care training.

Midwives Agnès and Brigitte.

Co-developed by Cuso International, the Canadian Association of Midwives, Ministry of Health of the DRC and the Société Congolaise de la Pratique Sage-Femme, the three-day workshop addresses compassionate care and patients’ rights.

Midwife Agnès Bitshilualua has delivered countless babies over her two-decade career. A mother to eight children herself, she’s seen a noticeable shift in the attitudes of medical professionals. “In the past, our rights as mothers weren’t always respected. If you asked for something, the midwives would ignore you,” she says. “This training gave us the idea that women who give birth have rights that we need to respect. Every time I do something, I have to ask for the mother’s opinion. And if she refuses, I stop.”

Dr. Mamisa Kachelewa, who works at the Clinique Mère-Enfant de Bahumbu in the Matete health zone, says this rights-based approach has had a direct effect on patient care. “We are really feeling the impact of this training,” she says. “The midwives are much more patient when they’re caring for the mothers.”

As she speaks, a midwife tracks down an interpreter to explain hemorrhage prevention to an English-speaking Nigerian immigrant mother, while another sets up a privacy screen for a patient and a third perches on an empty bed for a chat with a wide-eyed 18-year-old holding her first child. The mothers share stories of attentive, caring midwives. The result is an increase in the number of mothers who are choosing hospital births.

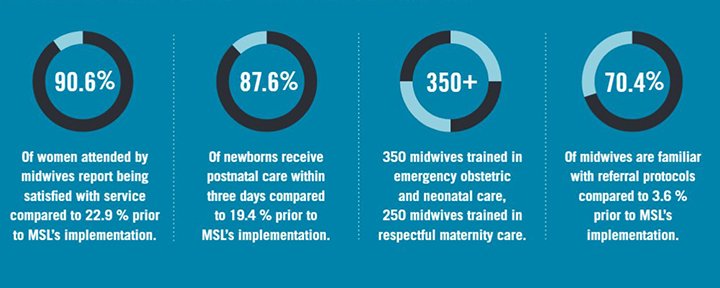

When midwives have access to the resources and training needed to do their jobs, everyone benefits. Data collected 2016-2020, DRC.

“When I went to give birth to my first child eight years ago, the midwives scolded the women and didn’t allow my relatives to come into the ward with food,” says Noëlla Gbangwa. “This time, I was well received. There was always someone next to me saying, ‘You can do what you want.’ If I have more children, it will be here.”

And it’s not only moms and babies who are benefiting. Fathers, too, are taking more active roles. “We used to say that if the father was there, the mother’s labour would take longer, and so we should just leave her in peace to deliver,” says Dally Ngyama, a nurse and health advisor.

Midwives celebrate International Day of the Midwife in DRC.

When his wife became pregnant with their second child, he decided to become more involved. He attended appointments, listened to the doctors and joined his wife for the delivery. The experience transformed Dally’s approach to prenatal care.

“It wasn’t easy, but everyone was telling me not to be scared. I was there talking to my wife the whole time. I loved being able to do that. And then they delivered a beautiful baby boy and we saw him,” he says. “Ever since, I’ve started to tell fathers that it’s important to approach pregnancy and birth together, starting with the first prenatal care appointment. It’s in their interest to know what is going to happen and how to prepare.”

Midwives Save Lives is a four-year initiative in Benin, DRC, Ethiopia and Tanzania. Led by Cuso International in partnership with the Canadian Association of Midwives and local midwifery associations, MSL is contributing to the reduction of maternal and newborn mortality by improving the supply and demand of health services and strengthening the work of midwives’ associations. MSL is funded by the Government of Canada through Global Affairs Canada.

Story and photos by Ruby Pratka, MSL Volunteer Communications Advisor